The new China playbook

The new China playbook: why a cultural shift not a technological shift is enabling China to outpace the West in both innovation and entrepreneurship

Welcome to China

It’s a pleasant and sunny March morning as we walk out of the Shangri La Hotel in the Futian District of Shenzhen, jump into an EV taxi (all 20,000 taxis in Shenzhen are EV, produced by BYD) and drive towards the electronics markets on Huaqiang Road where one of our Learning Journey partners, DST, is headquartered. If you are unfamiliar with DST, they manage a fleet of electric commercial vehicles (small to large trucks) that they lease to the largest logistics companies in China such as SF, Alibaba’s CaiNiao, Ikea and JD, one of China’s largest e-commerce platforms and the 19th largest (by market cap) tech company worldwide.

As we walk into the building we navigate around a construction area into a modest lobby equipped with two small rickety elevators that are each missing a few buttons. Once we make it up to their office we sit down with Shen Yu, the Head of Strategic Planning who informs us that they just hit the 23,000 vehicle mark for their EV fleet. This is big news and very exciting - needless to say, we were floored. However, Yu quickly calms our excitement by saying in an even tone, “we are still growing and patience will be necessary to continue ‘rapid growth’ over the next few years, but vehicle and driver data collection is at an all-time high.”

And it’s his reaction or lack thereof that is the most telltale sign of the Chinese entrepreneur mindset. If this was a US or EU company these growth numbers would merit a ‘bottle popping’ or bragging moment. It’s besides the point that we can’t even draw a 1:1 comparison with the European or U.S. EV freight/commercial vehicle market since Mercedes Benz, Freightliner, MAN, and other manufacturers are just now releasing eTrucks.

To put DST’s fleet into perspective (and why we were surprised he wasn’t over the moon with the growth numbers), they have more EV’s on the road than all Tesla’s sold in Europe in 2017. Even the much lauded StreetScooter (acquired by Deutsche Post and DHL), a light-duty commercial EV, only has 10,000 vehicles on the road.

DST’s dashboard showing their fleet of 23,000 vehicles, which they track in real-time.

This one interaction highlights some of the prevailing factors driving the success of Chinese technology, entrepreneurship and innovations that we’ve experienced first-hand over the last few years visiting Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen with our clients. We’ll dive deeper into these later, however the factors aligned to this interaction are: 1) scale, 2) culture (pride, modesty, patience), 3) data collection at all costs and 4) appearance. Appearance being one of the most distinguishing factors when you compare the China startup mindset vs the West’s. What you won’t find at these startups in China are the fancy offices, ping pong tables, gaming rooms or catered lunches. In China, they speak success in ‘numbers’ not office amenities.

If you take away one thing from this editorial it’s that China is not the West. We’ll draw upon our recent Learning Journey, in Shenzhen in particular, to illustrate why we can’t use Western thinking to judge where they’ve come from and where they will go. In this editorial, we’ll only briefly use Silicon Valley as a reference point, a technological contemporary of sorts — not a direct competitor or challenger. Most importantly, as we dive into specifics on where China has succeeded and is currently competing, we’ll draw comparisons between China and both the US and Europe as a whole. Our editorial format is organized as micro-stories and lessons to bring together many different topics and vantage points, providing the best possible overview.

Silicon Valley, the perpetual comparison

During Reid Hoffman’s (Founder of LinkedIn) Master’s of Scale podcast in 2017 (Episode 9), he spoke with Linda Rottenberg from Endeavor about one of the more popular and contentious questions often asked by our corporate clients and startups partners alike, “the next Silicon Valley is….?” Reid mentioned L.A., Tel Aviv, New York, Boston, London, and Berlin. However, he then boldly stated:

“It’s not that this contender might give rise to the next Silicon Valley. It has already given rise to the next Silicon Valley, and arguably, multiple Silicon Valleys. Beyond Silicon Valley itself, I believe that the next Silicon Valley is undoubtedly China.”

Reid couldn’t provide a specific destination in China, but rather rattled off as many as five cities: Shenzhen, Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Chengdu. This was an astute observation in 2017 and still holds water today. But is China really the next Silicon Valley or as Reid stated, the current Silicon Valley?

Let’s start with the biggest question that comes to mind for those of us in the west — can a politically singular country, addicted to growth (and success), with millions of subcultures, and a new appreciation for individuality (and personal identity), successfully maneuver towards software and hardware excellence that not only rivals the ‘Valley,’ but exceeds global expectations? What role will government play and what has been its role in pushing innovation forward in a country that only 40 years ago was a country of farmers? Silicon Valley, even with all of the criticism it has recently earned from the public, U.S. and EU legislators, and activist groups, has exceeded global expectations — it is the benchmark for a technology hub in every sense of the word.

A new benchmark

If we define Silicon Valley’s ‘benchmark’ criteria as ‘software and hardware excellence’, then China is more or less on par with the Valley — ahead in some areas, and behind in others. You could also argue that innovative business models, creative thinking, role models, a local (and large) venture pool and international prowess would also be valuable criteria. Let’s take international prowess as an example. We could define this as what percentage of software or hardware is ‘shipped’ to the world for global consumption. 90% of the worlds electronics are produced in Shenzhen, and that includes smartphones. Even more astonishing, per our partner David Li, Shenzhen smartphone brands make up close to 65% of the global market, of which most brands those of us in the West aren’t even familiar with because their markets are in Africa, SE Asia and other regions. However, if we were to look at software development, although China has created amazing software products like WeChat, they have not yet produced a Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Google, Amazon, Salesforce, Slack and an endless other cohort of software products being utilized around the globe to power everything from consumer smartphones to global enterprises.

China is domestically ahead, but globally behind (in terms of scale — not UX design, etc.). We think this will change, but for the time being, Silicon Valley has exported internet platforms throughout the world in a way that no community, city or country has rivaled, yet.

But at this point, we have to stop ourselves. We could debate and compare all day long. It would be a tedious exercise and likely not result in more than a checklist, and you (as a reader) would only be prepared to answer the same question that has already been posed too many times.

Why is this the wrong question (sorry, Reid) to ask?

There is only one Silicon Valley, and making any comparisons is already presumptive that a new burgeoning technology hub will a) require the same criteria to be successful in today’s global marketplace and b) be a copy of the Bay Area. Yes, Chinese entrepreneurs, real estate, etc. have been accused of ‘copying’, however this chapter of being the world’s copycat is largely coming to a close.

Answers abound in the form of “the _____ of _____.” Similar to the overused “the Uber of ____.” (please don’t utter out loud). Silicon Valley Part Deux, should not be: “Shenzhen is the Silicon Valley of Hardware.” Although, this might be true in very broad strokes, it misses all of the aspects which make Shenzhen extremely unique and very different from Silicon Valley.

So let’s reframe the question.

Why is China ahead (not using typical Silicon Valley criteria)?

How are they pioneering in their approach to technology?

What is the competitive advantage? Hint — it’s cultural.

To be bold, let’s boil this down to: How will China define the future?

Exciting, right? We thought so as well.

“Success depends upon previous preparation, and without such preparation there is sure to be failure” — Confucius

China’s plan for future growth

Daniel Burnham, the renowned architect, said “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.” China embodies this, top down and bottom up — and their plans have become synonymous with their fast rise to becoming the number one economy in the world. Currently, China is at the tail-end of their ‘Thirteenth Plan’, although they’ve now decided to use the terminology ‘Guidelines’ in place of ‘Plan’ as it has a less strict connotation. Each ‘Plan’ cycle lasts 5 years and as part of the Thirteenth Plan (lasting until 2020), two policies showcase the path the government would like its citizens to chart: 1) “Everyone is an entrepreneur, creativity of the masses” and 2) “Made in China 2025”. As a side note, I wrote a related piece, “Why “Made in China” is the “Made in Germany” of the future” in January 2017, which sheds light on how they are creating their own products and services rather than copying from the west.

There are many sub-plans and goals that track back to these two policies ranging from areas like 5G mobile technology, seed breeding, robotics by 2020, and becoming a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030. Electric vehicles are one of the most important pillars of Made in China 2025.

To meet the government’s mandate for EV’s for example, over 500 electric vehicle companies have launched since 2015 to cash in on the subsidies. China today has five of the top ten EV companies in the world (BYD, BAIC, SAIC, Geely, Chery). China’s EV related goals have already yielded successes and catapulted the country to the global leader in EV’s. More EVs were sold in Shanghai last year than in Germany, France, or the U.K. (Bloomberg). And companies like BYD, which is headquartered in Shenzhen, outsells Volkswagen and Hyundai-Kia combined globally in EV’s. BYD has transformed itself from its humble beginnings as a manufacturer of batteries for brick-size cellphones to becoming a top five automotive OEM in China with 250,000 employees, selling 30,000 EV’s per month.

Our market experts had to chuckle at the recent unveiling of the VW ID Roomzz concept at the Shanghai Motor Show, which is set to debut in 2021. VW, although respected and popular amongst Chinese consumers is late to the game with the NIO ES8 SUV already on the market. NIO, one of our Learning Journey partners, ES8 SUV is one of the fastest production EV’s on the market. As part of these plans, the government ensures that all parties working towards the successful implementation of the plan are set up for success, right down to the consumer. The cost of a license plate for an internal combustion car in Shanghai is $14,000, versus $0 for an electric vehicle license plate.

Visiting the NIO House in Shenzhen. Pictured in front is the EP9, the fastest EV supercar in the world, and the ES8 SUV in the background.

Government money talks

To say that the Chinese government has been generous in funding these plans is an understatement. The government’s latest venture capital fund is expected to invest more than $30 billion in AI and related technologies within state-owned firms with the goal of becoming a world leader in artificial intelligence (AI) by 2030, with the aim of making the industry worth 1 trillion yuan ($147.7 billion). Nanjing, capital of China’s eastern Jiangsu province, recently pledged nearly 16 billion USD to build a smart economy based on artificial intelligence.

If we compare this to Germany’s three billion EUR investment announced by Chancellor Merkel, this is a literal drop in the bucket. This also pales in comparison to the European Union’s 1.5 billion EUR for the creation of the EU AI Alliance. It’s almost laughable given the studies that show that Europe has to play catch up given their current position in patents, talent, and data architecture. Within the AI space, China has caught up in patents but still trails in talent, of which most (upwards of 70% globally) is based in the U.S. However, this will change. Chinese cities are now incorporating AI education into their school curriculum and last year published a school textbook on AI. This educational push, especially at such a young age, will deliver China the future AI talent they’ll need by 2030 to be the global leader in the field.

In our experience, most if not all of our partner startups in China have been able to secure a mix of space, funding (via subsidies), and licenses from the government to propel them towards success. If your product or services shows signs of traction (DAU/MAU, local support, etc.), you are almost guaranteed a helping hand from the government. Licenses also play a critical role. Within some industries, such as digital maps and telematics, Navinfo, one of our Learning Journey partners and China’s largest digital map provider (fourth largest in the world), has been able to secure one of ten licenses awarded to companies in the space.

The word “government supported” for most often conjures images of red tape, stifled innovation, or the feeling of “DOA”. There rightfully exists a negative connotation or association whenever we think about governments getting involved with innovation let alone with the private sector. But if there is one place we’ve seen it work, it’s in a place we wouldn’t expect, China. Richard Appelbaum, a market expert on China, points out in his new book, Innovation in China, that “the often contradictory blend of heavy-handed state-driven development and untrammeled free enterprise” is a catalyst pushing innovation forward. Startups not only seek it out but often draft their business model based on government plans and initiatives. The West, both the U.S. and Europe, could learn from this approach. Clear plans and financial support is required for growth in this new century.

In many ways, this creates a unique competitive landscape in China. As a successful hardware or software company you typically only have a couple ‘real’ competitors that are of equal or lesser size. If a new competitor enters the market that could rival you, it more than likely will be from a completely different industry or sector. If Alibaba or Tencent think about getting into the industry that you lead, then it will be a significant challenge. As most large companies in China can’t grow significantly once they’ve saturated the domestic market, they turn their attention to other industries. This is starting to change as ByteDance, Tencent, Alibaba and others are pushing into global markets.

“A superior man is modest in his speech, but exceeds in his actions” — Confucius

Although the Chinese government’s long-term planning and involvement in ‘capitalist experimentation’ has been an incredible catalyst for the growth of economic opportunities for its population, it’s had to pull off an incredible balancing act to ensure socialist values endure culturally (in lieu of having the largest middle-class population in the world), and play a delicate game of free enterprise and international accessibility (in the form of JV’s between Chinese and foreign brands). This ‘balance’ that has defined the last decades in China we believe will not only remain, but likely become even more prominent — the top priority for Xi Jinping in the near future. The age of “necessary balance for success,” as we’ve coined the term, is upon China.

Amongst the many elements that keep this balance steady, the CCP’s priority will likely be the match of human capital with future plans or guidelines (due to impending commercial and industrial transitions). Chinese human capital is already well adapted for skill set transitions. Factory workers have been retrained or reskilled as hardware experts employed by solution houses and urban (and now rural) youth are creating new business models out of thin air. A ‘digital maker class’ has emerged, that is focused on turning passions into opportunities, at a scale and speed far exceeding anything we’ve seen in the West.

However, internationally China will need to invest more than ever in ‘balance’ as their future relies on the global economy and not their domestic market. China has garnered headlines for its social credit system (taking effect in 2020), the world’s most extensive and sophisticated online censorship system (likely +2.5M people strong), and it’s state surveillance apparatus. It’s important to point out that the West has taken similar steps. Facebook’s ‘content moderators’ (via contracted services providers such as Cognizant) number in the thousands and China’s intelligent monitoring systems have been purchased by “18 countries — including Zimbabwe, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Kenya, the United Arab Emirates and Germany.” In light of these international headlines, and to ensure “necessary balance” remains a priority internationally, government sanctioned organizations such as the Confucius Institute promoting Chinese language and culture have popped up everywhere since 2004. Their stated mission is to satisfy the soaring global demand to learn Chinese. By our accounts, we estimate that there are now close to 800 institutes worldwide with as many as 30 locations in some countries.

A new culture emerges: China youth

China is probably most misunderstood internationally for their culture. Chinese culture is more complex than what often meets the eye. And a dramatic shift in their culture is now underway. China is now dominated by its youth culture (16–36) in urban centers. And, Chinese youth are as motivated as ever to not miss the next big opportunity. While visiting our Learning Journey partners at DJI we had the opportunity to hear about the development of their industrial drone products (which will likely outpace their consumer drones in sales by 2020) and what struck us the most was the story of the Head of Product of the Inspire drone division. He started as an intern, had the initial idea for the Inspire drone, was supported in prototyping and shortly thereafter (within one year) became the Head of Product for the entire Inspire product line. It’s important to note that the median age at DJI (in China) is 28. This is not much younger than the median age in Shenzhen which is 32.

The DJI example highlights the tenacity of China’s youth. One of our close Learning Journey partners, Kevin Lee, the COO of China Youthology, says of the current generation, “they only know growth… they only know good times.” China Youthology is the leading expert in studying China’s youth culture and supports Tencent and Alibaba in developing new products and services for their customers based on user data garnered through their respective platforms. In our discussion with Kevin, he went on to say “they’ve seen their Aunts and Uncles work-hard and achieve success and therefore believe that hard work guarantees success.” However, with GDP growth slowing, hard work might not be the only element necessary for success. “Hard-work” or at least the working-hours defined as ‘hard-work’, have also come under fire from younger employees, whom have discounted the 996 work culture evangelized by Jack Ma and other tech CEO’s. For reference, 996 refers to 9am-9pm 6 day work week. Kevin believes work-world ‘disillusionment’ in part stems from the “me generation’s” new-found ‘self-identity’ and ‘individualism’ — he estimates that there are more subcultures now in China than in Europe or the U.S., which upon our view into the market we can only agree with.

At DJI’s HQ showroom. Pictured are the Inspire (non-consumer) drones.

Opportunity is everywhere

The notion of ‘opportunity is everywhere’ in China is not myth, but very real. Amongst the many entrepreneurial stories we’ve gathered during our travels through China’s tech ecosystem, one that continues to fascinate us and our clients came from our discussions with David Li, Founder of the Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab and Shenzhen’s de-facto open innovation leader. It’s one of the most inspiring examples of raw entrepreneurialism driven in part by the e-commerce ecosystem that exists in China. The sleepy village of Shaji with 50,000 inhabitants in the north of rural Jiangsu is home to one of China’s largest e-commerce furniture companies. Hard to believe, right? In 2005, while honeymooning in Shanghai, Sun Han from Shaji discovered Ikea and flat-pack furniture. Seeing the demand amongst the emerging middle class in Shanghai, he went back to Shaji and worked with local carpenters to develop the first furniture prototypes and put them online for sale in their new Taobao shop (a mix of Amazon and eBay, owned by Alibaba). They sold out. In 2010, revenue approached 50 million USD. Today, their revenue is 2 billion USD, and most, if not all of the village works for the furniture company selling in over 6000 Taobao shops. Every old farmhouse in the village has been repurposed into a production facility and many of the villagers now can be seen driving BMWs and Mercedes. This phenomenon has come be known as the “Taobao Village,” of which there are more than 2,500 Taobao villages across China today generating close to 50 billion USD.

From right, David Li of the Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab with authors Ryan McLaughlin and Brian Gale.

Women leading the charge

One cultural aspect that has not changed much since the Cultural Revolution is the role of women within the workforce, which extends to the technology industry. This is in stark contrast to the West. In China, 46% of the tech workforce is female compared to the U.S. at 24% or Germany at 16%. This extends to C-level jobs in tech as well. “When asked how many women have C-level jobs at their company, 54 percent of U.S. tech companies answered “one or more.” Similarly, 53 percent in the United Kingdom answered “one or more.” In China, nearly 80 percent answered “one or more.” (via SVB study). And, among new technology startups in China, 55 percent are being founded by women. And since we’re a WeWork member, we found it great that China also happens to be the only country where women outnumber men at WeWork. More than 51 percent of WeWork China’s members are women, compared with an average of 47 percent worldwide.

China’s cultural narrative is ever-changing and evolving. A significant portion of the population is aging, a slowing birth rate (possibly a negative birth rate by 2030), and a divorce rate that is on par with the U.S., are signs that Chinese social demographics are starting to match China’s economic status in the world. Some of our market experts have even speculated that a ‘singles’ tax, that would tax singles to compensate families with children, could be put in place to spur birth rate growth. The rationale being that the same government that enacted a one-child policy can also enact a three-child policy.

Downturn ahead?

Some experts are starting to warn about a downturn. Recently, Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and a non-resident senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States stated “China’s inability to take the opportunity to do the right thing” during the current trade war with the United States could cost the country dearly in the form of a recession that “will become the worst in recent Chinese history.” China has been deferring the boom and bust cycle and it could come crashing down.

We believe, that a large-scale recession could be the most substantial ‘opportunity catalyst’ for entrepreneurs that China will have ever seen. Some legacy industries in China will suffer for a few years, however, new business models and technologies will blossom. If a recession comes to pass, it will be a blessing in disguise. Why?

When we look to the 2008 GED (global economic downturn), Uber (2009), Airbnb (2008), Pinterest (2009), WeWork (2010) were all launched in the U.S. during the downturn. These businesses are all IPO’ing this year, or in the case of Pinterest and UBER have IPO’d successfully already.

We believe that a downturn in China, given the current cultural conditions, which are surprisingly similar to those that existed in the U.S. during the last GED and that led to an influx of digital platform companies being founded, will produce the next entrepreneur boom in China. Some of these cultural conditions that are in-line with the last U.S. downturn are a millennial generation that has their own (and very individual) philosophy regarding ‘liberal thought’ with a focus on environmental activism and a sense of overall greater purpose in where they fit in the world.

For the world vs for country

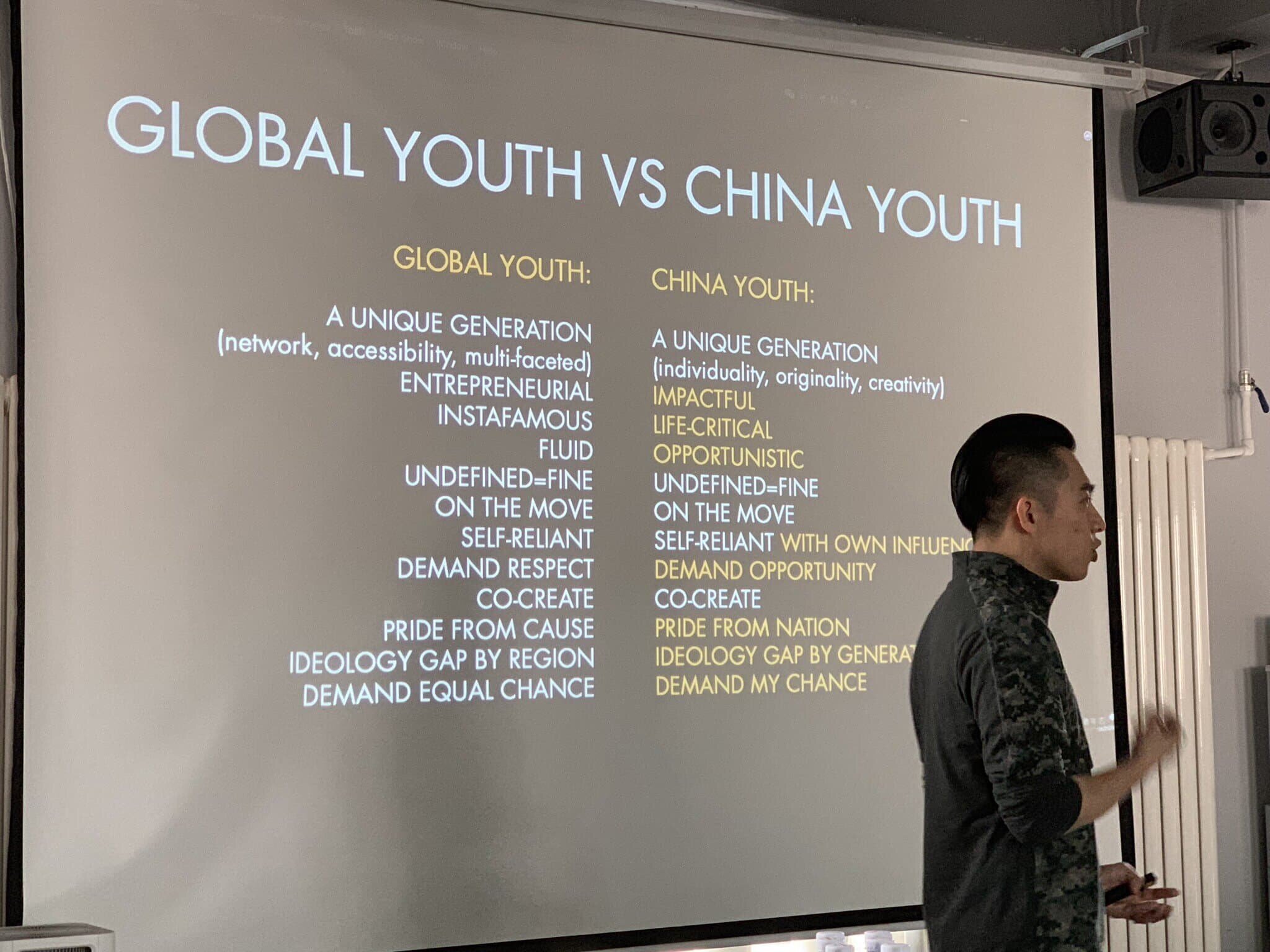

It is important to understand that Chinese entrepreneurial motivations are tantamount to those in the West, however there are subtle nuances that are cultural in nature. Most western entrepreneurs motivations are financial, autonomy and good for the world. For many entrepreneurs in China this is similar, however replace ‘for the world’ with ‘for our country.’ Most Western entrepreneurs are not starting businesses for the U.S., Spain, Germany, etc. This is echoed by Kevin Lee who describes the global youth as having “pride from cause”, whereas in China, it’s “pride from nation.” Although these new entrepreneurs will continue building businesses ‘for China’, they will be more focused on building a business with a global footprint from the start, vs. domestic first and then international. We also think more will come from rural areas.

Kevin Lee of China Youthology explaining the difference between global youth cultures and the youth culture in China.

Not only will the Chinese entrepreneur evolve in the coming years, but the Chinese consumer will as well. Just as the iPhone has fallen out of favor in China and resulted in a downward sales trend for Apple, many Western brands will also have to face the music, particularly European OEM’s. Half of global VW sales in 2018 were in China. Over a third of Audi’s sales for 2018 were also in China, and BMW and Daimler are in similar positions, selling 30% of their vehicles in China. Looking ahead to EV’s, China’s ownership of the battery value chain can eventually trump European ‘brand cache’, and in some cases it already has. The rise of the high-end Chinese brands like NIO in the automotive segment, or the NUO in luxury hotels, and even phones like the Huawei P30 Pro (900 EUR) or beverages such as coffee, where Starbucks is under pressure by Luckin Coffee, who recently received an investment of 150 million USD from Blackrock and others, exemplifies this point that Western Brands will have to fight harder for market share in China — gone are the days where Western brands are synonymous with luxury and desirability. Western brands reliance on the Chinese market, coupled with a new suite of cross industry home-grown high-end Chinese brands with growing domestic demand could lead to a sales collapse of some Western brands in China (it already happened for Prada whose earnings are down 50% over the last years due in large part to their China sales).

“They must often change, who would be constant in happiness or wisdom” — Confucius

The entrepreneurs marketplace: Shenzhen

While walking through the narrow booths of the Tong Tian Di Telecommunication Market, which is also known as ‘iPhone market’, the buzz of customers haggling and deals being made is palpable. Shenzhen’s electronics markets in the Huaqiangbei district, of which there are over a dozen, have every imaginable hardware component on hand to build everything from phones and tablets to drones and Playstations. Each electronics market specializes in a particular set of components and all factories in and around Shenzhen have a booth in the markets. Within a few days you can make your way around and build your own phone, as we, the Wall Street Journal, and countless other visitors to Shenzhen have done.

Shenzhen’s electronics markets in the Huaqiangbei district are a one-stop-shop for everything you need to build and rapid prototype. This is one of thousands of booths where you can pick up literally anything electronic.

In addition to the electronics markets, Shenzhen is full of industrial design studios that will help you refine your product design and prototype your concept in a short amount of time and at a very low cost. How short and inexpensive are we talking? For a smaller product, let’s say a version of a smart watch, roughly 5000 EUR with a one week delivery date. Compare this to an industrial design studio in Berlin, which will require 150,000–200,000 EUR and 9–12 months to deliver. These are actual costs that we sourced from a local studio. The level of industrial design in Shenzhen is nothing to laugh at today. Shenzhen related designs win 40% of red dot awards.

The electronics markets along with industrial design studios are the physical manifestation of the innovative spirit driving Shenzhen, providing an endless component ‘tool chest’ for makers and tinkerers to develop new products at a moment’s notice. Although both of these entities are essential to Shenzhen’s ‘maker society’, there are a handful of abstract and less tangible elements that contribute to the larger innovation ecosystem and allow Shenzhen to be a leader in hardware innovation.

One of these abstract elements is the ‘open’ mindset around entrepreneurialism in Shenzhen. David Li believes “Shenzhen works because it doesn’t have gatekeepers for entrepreneurs — there is no innovation campus that tells people if they are entrepreneurs or not. All people are entrepreneurs.” He added to this, “everyone cooperates, everyone specializes, everyone wants to make money — if I’m making a smartwatch I need to buy components, those component developers win and those that see my product and build similar create more market for my products, so everyone wins.” The Shenzhen entrepreneur is not interested in making the next iPhone, but how he or she can deliver the next big innovation to Africa, SEA, and South America.

An abundance of human capital

Another less tangible element is Shenzhen’s human capital. The talent pool of hardware specialists has almost been magnetically attracted to Shenzhen. While spending time at the Blue Bay Incubator, HKUST (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) in Shenzhen we asked Calvin Zhang, founder of Incus a novel hearing aid startup, why Shenzhen was the best place for them to be located. He said, “the best talent is here for hardware and software blending together in all of China and probably the world.” It’s also the reason that companies stay in Shenzhen. DJI, which we mentioned earlier, was incubated out of the Blue Bay Incubator and is still headquartered in Shenzhen.

At the Blue Bay Incubator, where DJI was incubated.

Speed to market is essential

Probably the most important of the abstract elements, and mentioned often amongst our Learning Journey partners in Shenzhen is the ‘Shanzhai’ way of product development. Literally translated, ‘mountain hideout,’ this term originates from the Hong Kong factories that sprang up 50 years ago in the mountains around Hong Kong and would produce many versions of a product to understand it’s traction in the market. Shenzhen has taken this a step further and uses Shanzhai as their operating model: produce ten similar products, launch them all at once and see which performs the best amongst consumers. Mass produce the best seller and kill the other nine products. This process would be a hard-sell for companies in the west, which would not want to release a ‘failing’ product. Speed is also an important factor here. Moving fast is not reserved for particular processes or products but for everything. Keep in mind 70% of the unicorns in China today were not created three years ago.

Deng Xiaoping’s Special Economic Zones along with the electronics markets, industrial design studios, mindset, talent pool, and way of working has allowed Shenzhen to blossom from a 30,000 person string of villages into a 15 million person ‘technology first’ metropolitan area in 35 years. And of these 15 million people, roughly 800,000 are millionaires — that’s more millionaires than London and New York combined. And again, David Li put it best when he said, “It’s not research that makes Shenzhen great in innovation, we only have two universities and we just doubled that number last year, it’s our dynamism.” This dynamism is what makes Shenzhen and China, unique. This is not a Silicon Valley export placed conveniently within arm’s reach of the Chinese entrepreneur but a native characteristic of this ecosystem.

View from the bottom of the Pingan building, a 115 story skyscraper that dominates the skyline.

The fact that most (over 50%) of the Western business contacts in our network we interact with (including some very innovative companies) have never heard of Shenzhen and less than 1% have been to Shenzhen is scary, astonishing, and showcases the West’s inability to look beyond Chinese clichés and innovation ‘egos’.

It’s the West’s turn to change

The West will contend with an even greater balancing act ahead. From regulation of hardware and software applications (see ‘break up’ of big tech in the U.S.) to the availability of private and public funding (lack of funding in the EU), to an ongoing trade battle with China (U.S.), the West will have to walk a fine line to compete. And it’s a very hard line to draw. The biggest challenge for the EU in particular will be to draw a massive zig zag line, because there is no black and white — only gray.

China is not ahead or behind, it’s well prepared, hungry, and open. And it’s not Silicon Valley.

When Ried Hoffman spoke to Andrew Ng, the former chief scientist at Baidu (China’s Google), Andrew said, “you can’t really appreciate the pace of innovation that’s taking place across China’s major metropolises, until you see them for yourself.”

I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand. — Confucius

END

Interested in the ‘real China’ experience?

If you’re interested in learning about the China technology landscape, we would like to invite you to reach out to schedule a Learning Journey to Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing, so you can gain true perspective on innovation happening in China today. If interested, please contact ryan@mcl.digital.

About the authors

Ryan is the founder and CEO of MCL.digital, an innovation consultancy that is focused on Digital Transformation through Learning Journeys, Design Sprints and Branded Innovation Events and Programming.

Brian is a strategic advisor at MCL.digital and co-founder of BTblock, a leading blockchain & cybersecurity consultancy firm with offices in Denver, New York, Boston and London.